Silencing Our Most Marginalised Women By Stripping Away Their Voting Rights

By Awatea Mita (justice scholar and kaiwhakatuhono for Aotearoa Free From Stalking)

Aotearoa New Zealand often touts a strong history of supporting women’s rights, taking great pride in being the first country to grant women the right to vote in 1893. However, we have regressed, and it might come as a revelation to some that universal suffrage, that cornerstone of democracy and representative government, is no longer upheld in our country.

The reintroduction of a complete voting ban for people in prison will only worsen the deprivation of this fundamental human right. In 2017, the Department of Corrections found that a shocking 75% of imprisoned women had experienced family violence (FV) and/or sexual violence (SV) and 66% of the women had experienced physical intimate partner violence (IPV). Stripping away their voting rights effectively silences the most structurally marginalised women in our country.

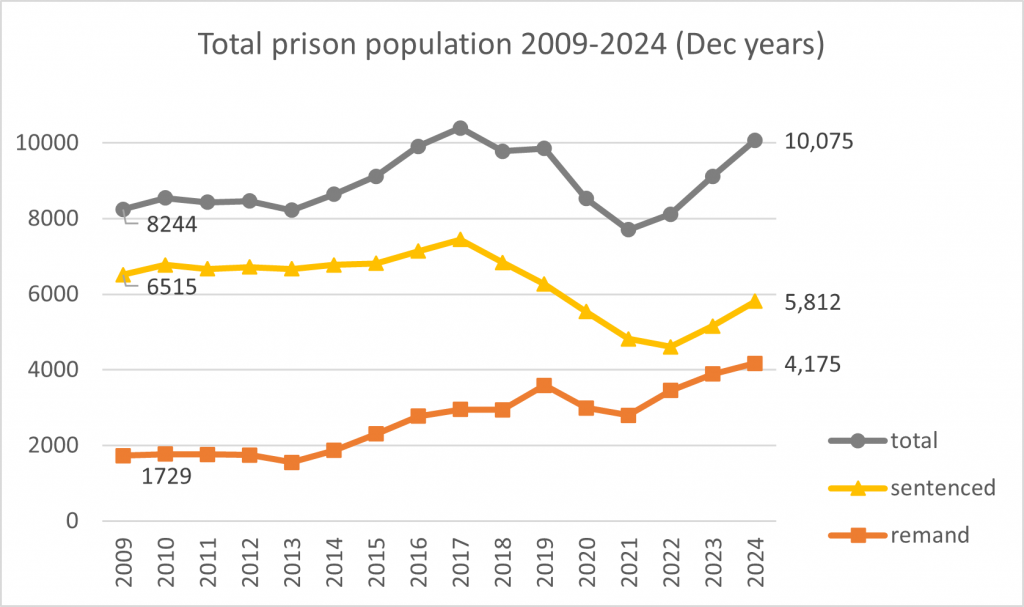

Wāhine Māori are consistently concerned about ongoing colonisation and its profoundly detrimental impacts on both people and the environment. Criminal justice continues to be a critical area of focus. Māori are subject to over-surveillance, over-policing, over-arresting, over-charging and over-convicting with harsher and lengthier sentences. Māori are disproportionately more likely than non-Māori to be incarcerated for low-level offences. In 2022, Māori men were over six times more likely to be in prison than non-Māori men, while Māori women are almost 11 times more likely to be in prison than non-Māori women. Significant increases in the number of wāhine Māori in prison can be traced to two key pieces of legislation: the Sentencing Act 2002 and the Bail Amendment Act 2013. The Sentencing Act 2002 removed suspended sentences, failing to thoroughly weigh-up the profound impacts this change would have. The inherent tendency of patriarchal systems to neglect the intersection of gender and ethnicity, failed to consider the unique factors that constitute women’s offender profiles. For example, women are less likely to commit violent crimes. Women who are less likely to reoffend, and particularly those with children, would no longer benefit from a suspended sentence. Instead, the Sentencing Act 2002 increased the likelihood of women receiving prison sentences. Wāhine Māori, along with their children, shoulder the most significant burden arising from this legislative change, especially when we acknowledge that the rise in imprisonment was not preceded by an increase in offending. The graph below shows numbers of all prisoners, sentenced or on remand (before trial or before sentencing) from 2009 to 2024 (December numbers).

source: Dept of Corrections

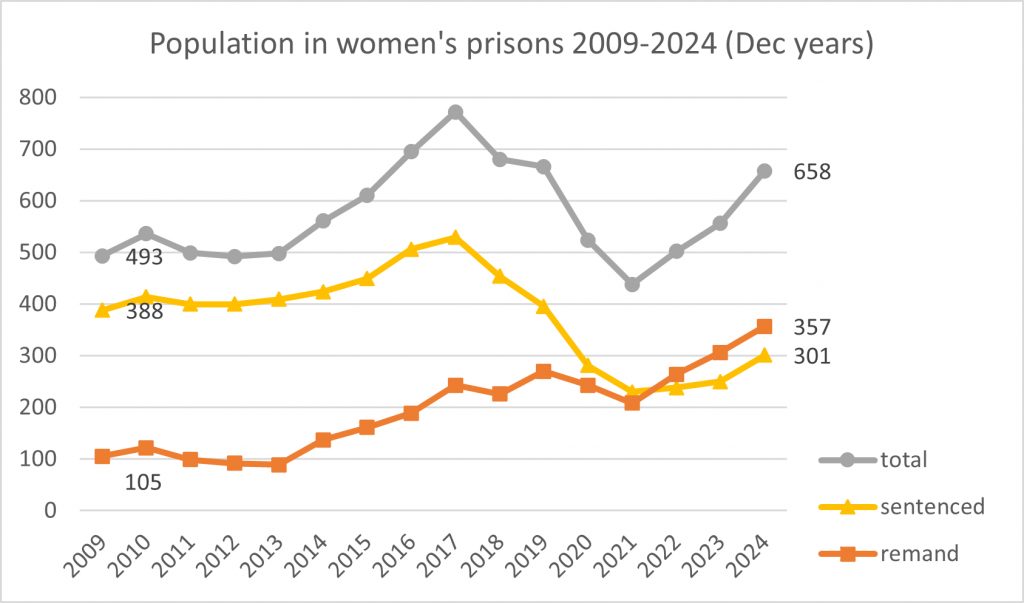

From 2013 onwards there was a steep increase in the number of people remanded in custody following the introduction of the Bail Amendment Act which required defendants to prove their innocence and/or appropriateness to be bailed at large. The Ministry of Justice projections pointed to an increase of 50 extra people being held on remand as a result of the Bail Amendment Act 2013. Three years after its introduction, by 2016, there were 1,500 additional people imprisoned on remand. suggesting that the focus of the Act extended beyond its original scope. In any case, it is clear that the projections for remand were grossly underestimated. The graph below shows numbers of prisoners in women’s prisons, sentenced or on remand (before trial or before sentencing) from 2009 to 2024 (December numbers).

source: Dept of Corrections

The number of wāhine Māori on remand increased eight-fold between 1998 and 2020. In 2013, at the time of the introduction of the Bail Amendment Act, wāhine Māori made up 59% of people remanded in prison, and by 2020 this was approximately 65%. What we can infer from these statistics is that wāhine Māori were significantly more likely to be held in custodial remand after 2013. Indeed, between 2013 and 2020 the number of wāhine Māori on remand had doubled.

As above, rates of gender violence experienced by women entering prison are extremely high. For far too many women, exposure to abuse begins at a young age and persists as part of an enduring continuum of violence. Women experiencing poverty and lacking access to education and work opportunities are more likely to experience reduced decision-making power, limited economic opportunities, and increased vulnerability to exploitation and violence such as IPV. This creates a significant power imbalance where they have less agency in shaping their own lives and the lives of their families. Economic hardship can also make it harder to leave abusive relationships. Additionally, women who experience IPV also suffer more mental health challenges. Such high numbers of IPV, FV and SV amongst imprisoned women, the majority of whom we know to be Māori, is reprehensible. Prisons, far from ensuring the safety of women, often retraumatise them, heightening the risks to their mental well-being.

Rather than investing in more comprehensive resources and support within the community to address gendered violence, prisons have increasingly emerged as a de facto solution for women whose lives have been derailed. There are many topics of debate when considering voting rights. Stripping away the voting rights of these women effectively silences the most structurally marginalised women in our country, and wāhine Māori are the most disproportionately disadvantaged, given the overrepresentation of wāhine Māori in prison. The detrimental impacts of these discriminatory outcomes are not confined to the women themselves, but also their children, the rest of their whānau and their communities. This is colonisation in practice; it shifts political power further away from tangata whenua, ensuring they have less control over their own lives and futures.

The last time a complete ban on voting rights for people in prison was implemented was in 2010, whereas previously only a partial ban existed for those with a prison sentence exceeding three years. The outcomes of the complete ban were clear a year later. After its introduction, the number of non-Māori removed from the electoral role doubled. As if that wasn’t bad enough, the number of Māori removed from the electoral roll increased ten-fold. Ten times as many Māori were removed from the electoral roll as a result of the blanket ban on voting for people in prison – five times the increase for non-Māori, in proportional terms. If one or both parents are in prison, and a household doesn’t vote, children never see anyone vote, and they are unlikely to vote as adults. A voting ban for people in prison is effectively racist and unconstitutional, punching down on Māori. Re-enrolment rates for formerly incarcerated people are also very low. High rates of incarceration for Māori translates into whole communities not voting. Removing voting rights for people in prison clearly affects all Māori.

Removing voting rights for people in prison does not contribute to crime prevention or increase public safety. It is arbitrary because two people can appear before the court with the same crime, the same offending history and demographics, and one might be sentenced to prison while the other is not. One person loses their right to vote while the other does not for the same crime. Instead, our prisons could actively encourage voter registration and educate people about civics. Upon release, these people could lead their communities towards greater political participation and engagement with the electoral process. A complete voting ban or partial voting ban on people in prison diminishes citizenship, prevents citizens from challenging disenfranchisement, rendering them powerless to resist the removal of their fundamental right to vote. The political voices of women in prisons must not be silenced. To fully acknowledge their inherent dignity, is to recognise their fundamental right to vote on policies that address their profound challenges and the pervasive gendered violence they endure; their voting rights must be protected.

How many of you participated in the Toitū Te Tiriti Hikoi? In this moment of significantly increased Māori voter engagement, participation and enrolments; despite global consensus to protect voting rights under international human rights law; despite clear legal findings that removing voting rights for people in prisons breaches human rights and Te Tiriti; despite very clear legal findings from the High Court that removing voting rights for people in prisons is unconstitutional; it is indefensible, and yet unsurprising, that the current government chooses to pursue an unjustifiable position on prisoner voting. If we don’t win this battle to stop the removal of voting rights for people in prison, then let’s show our political leaders at the ballot next year, by exercising our voting rights in favour of a government that will uphold universal suffrage, voting rights for all, including people in prison. Ngā manaakitanga ki a tatou katoa.

Click here to urge the government to keep prisoner voting rights, via Amnesty International.