Aotearoa Free From Stalking Submission Guide

Let’s make the new anti-stalking law as good as possible

Kia kaha, kia maia, kia manawanui!

We want a law to help survivors and whānau, and prevent stalking – this submission guide advises on how you can help.

Submissions and Parliament’s informal anonymous survey are now open on the Crimes Legislation (Stalking and Harassment) Amendment Bill until Thursday 13 February.

Click here for more info on the options to have your say.

Your voice matters. The select committee process is a rare moment for politicians and their advisors to hear real-life experiences from whānau and people from all walks of life. You may be/have been stalked by an abusive partner. You may have experienced stalking related to your gender, your ethnicity, your disability, your sexuality, your immigration status and/or your role at work. It can be useful for the Select Committee to hear about relevant lived experience and effects, if you feel comfortable sharing. Please note: Aotearoa Free From Stalking is not set up to provide individual advocacy or support. Free 24/7 national helplines are at the bottom of this page.

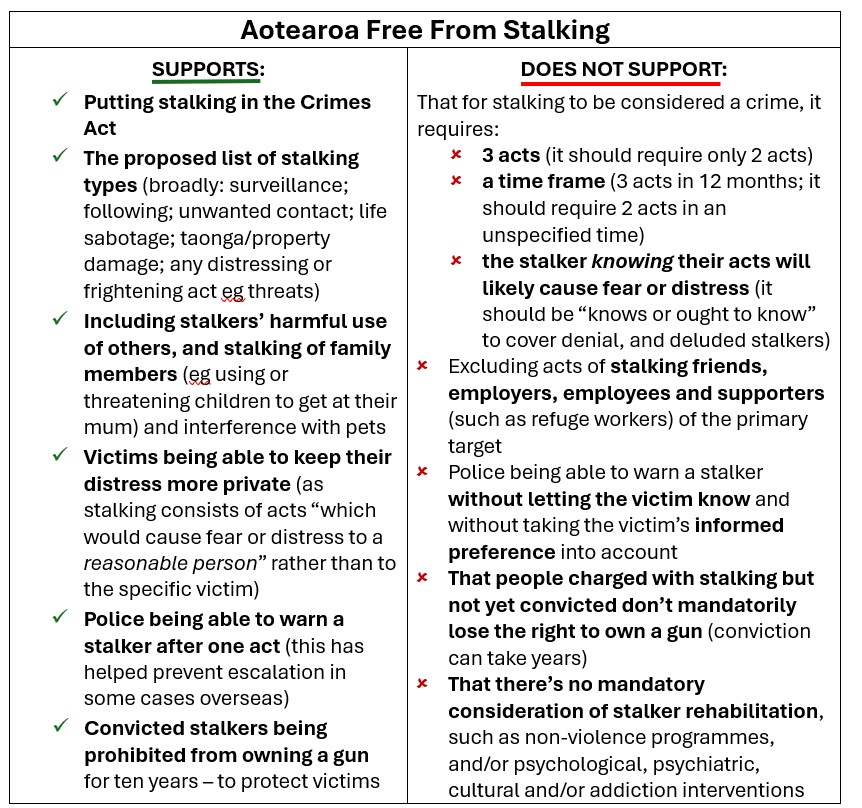

Overall, the Auckland Women’s Centre and our Aotearoa Free From Stalking campaign support the bill – but some things need changing in the bill to ensure it really does help prevent stalking and supports victim-survivors to be safe and free.

Below are some suggestions for you to consider putting into your own words, and to help jog your own ideas. A HUGE thank you to all the lawyers and violence prevention experts, including the Backbone Collective, who informed this guide. (All potential errors remain our own.)

At a glance:

- Let the select committee know you do not support the definition of criminal stalking as at least three (provable) acts within 12 months

Instead, stalking needs to be defined as a minimum of two frightening or distressing acts as is international standard, and is currently the case in New Zealand for harassment. Changing the definition of criminal harassment from two acts to three would be a backwards step.

- Victims should not have to wait until they have suffered three provable acts of stalking before the behaviour of the person responsible is officially unacceptable.

- Stalking does not have a timeframe, it can happen sporadically over years – the 12 month time limit should be removed. For example, a stalker imprisoned (for any offence) for longer than 12 months may re-start their stalking after their imprisonment has finished.

Relevant lived experience could include:

- someone who stopped stalking you for a year or more and then started again – how did you feel when the stalking started again?

- someone who carries out stalking acts usually once a year (for example, on an anniversary)

- stalking where it was difficult to prove exactly who was responsible, even if you knew who it was eg anonymous destruction of property (it is harder to prove three acts than two acts of stalking)

- Let the select committee know the courts must consider rehabilitation pathways for all people convicted of stalking

The Bill does not currently mention rehabilitation pathways. Although the Sentencing Act 2002 already allows the court to consider “programmes” and supervision if the court decides to do so in certain cases, the law should go further and state that for all people convicted of stalking – indeed, perhaps for all people convicted of any offence – the court must consider whether one or more rehabilitation pathways are appropriate – to increase the safety of all our communities. These could include (but are not necessarily limited to) evidence-based, culturally-safe, identity-appropriate and monitored stopping violence programmes and/or psychological, psychiatric, addiction and/or cultural interventions. The court does not need to use rehabilitation pathways in all cases but the law should state the court must consider such use.

- Let the select committee know you do not support the definition of criminal stalking requiring the stalker knowing their acts will likely cause fear or distress

Instead, criminal stalking should be when the stalker “knows or ought to know” their acts will likely cause fear or distress, or would be likely to do so if the victim or target ever found out about them. This is to cover:

-

- acts by delusional stalkers (such as fans/strangers who think their celebrity target actually welcomes their attention). As with other crimes, the law needs to make it clear that distressing and/and frightening stalking is unacceptable in all circumstances.

- stalkers pretending not to know their acts are likely causing fear or distress.

- covert tracking and surveillance that is not meant to be discovered by the victim.

Relevant lived experience could include any times when someone pretended that they did not know their stalking caused fear or distress for you, or for people connected to you – particularly when they were believed. It can also include the distress of any time you found out someone was tracking you covertly, digitally or in person.

- Let the select committee know you are concerned about allowing “reasonable excuse” as a defense, as it could be used by stalkers to avoid accountability

On the other hand, sometimes attempts to stop someone else’s stalking can themselves be interpreted as stalking. For example, stalking victims may use counter-surveillance as a way of protecting themselves, and so “reasonable excuse” could be a way of defending their vital self-protection. We think the select committee should consider including a high level of evidence necessary to reach the threshold of “reasonable excuse” in the bill, or removing the defense altogether. There are two other defenses in the bill which we think should be kept: “lawful purpose” and “in the public interest”.

Relevant lived experience could include any times when someone pretended that their behaviour was for a purpose other than alarming or distressing you. (eg communicating with children they co-parent with you).

- Let the select committee know you support convicted stalkers being prohibited from owning a gun for ten years but

that the Bill should also require people who are charged with stalking (but not yet convicted) to be prohibited from owning a gun

Currently, police can decide whether or not to revoke a gun licence from a person charged with an offence that may involve a prison sentence. Revoking gun licences from people charged with stalking should be a mandatory requirement, rather than a police decision,

in order to better protect victims and the general public. The bill includes removing permission to own a firearm (for ten years) from people who are convicted – but conviction can take years. During those years, victims need to be made safer by making it more difficult for their stalker to have access to firearms.

Relevant lived experience could include any times when you felt less safe because someone who stalked you or used other violence owned a gun.

- Let the select committee know you support stalking/ harassment being included in the Crimes Act 1961

Putting this offence in the same law as other violent offences will make it easiest for police and other criminal justice professionals to find and understand. The related offence of criminal harassment (Harassment Act 1997) has not been well used, and Aotearoa Free From Stalking understands that this is at least partially due to it not being in the Crimes Act.

- Let the select committee know you support the proposed list of stalking types

- It is good that the bill’s list of stalking acts covers an appropriately broad range of behaviour, including surveillance, following, unwanted contact, life sabotage, damage or interference with taonga/property and pets

- Is future-proofed so that stalking by potential future technology is covered (“A specified act may be done by or through any means whatsoever.”

- Let the select committee know you support the definition of stalking acts as those which would cause fear or distress to “reasonable person” rather than to any specific, actual victim

- Use of this phrase will limit the need for victims to prove fear or distress, and therefore protect their privacy.

- However, the bill also needs to include an instruction that the interpretation of reasonable person needs to take “context and circumstances” (or similar) into account, to ensure a “reasonable person” is not assumed to be a previously-unharmed blank slate with no history or background, and with the same social, financial, and/or physical power/resources as their stalker.

Relevant lived experience could include any times when your experience was influenced by your gender, ethnicity, disability income, sexuality, and/or parental status – eg the effects of already-existing PTSD on the experience of being stalked; or the potential social, safety and financial aspects of being ‘outed’ involuntarily as a Takatāpui or Rainbow person

- Let the select committee know you support that the definition of stalking acts including stalking family members as a way of stalking a primary target, and includes using other people to stalk the primary target (whether or not those other people know they’re being used in this way). Also let them know that the definition should also include stalking friends, chosen family and professional/voluntary supporters (such as lawyers and social service workers) as a way of stalking a primary target.

Acknowledgement of family victims other than the primary target – such as children threatened to cause fear and distress in their mum – is important to increase protection and reduce harm for all affected.

This category should also include friends and associates as well as family members of the primary target – for example, the bill currently does not mention people who are stalked because they are friends, colleagues, employees or supporters of the primary target, or their “chosen family” (which has specific importance inside Takatāpui and Rainbow communities and for people who cannot rely on biological families in ways others might be able to).

Currently, any stalking they experience due to their association with the primary target would be considered separately, rather than being seen as part of the same pattern of behaviour. It should be seen and treated as part of the stalking of the primary target.

Relevant lived experience could include any times you have experienced someone stalking your loved ones or associates, or you have been stalked because of your connection to their primary target.

- Let the select committee now you support police being able to warn a stalker after one act – but that:

-

- It must be clear that a warning is not the only way for someone to know their stalking acts are causing fear and/or distress

- The victim must be fully informed about what the warning involves and what it legally represents

- If the fully-informed victim strongly advises the police against warning the stalker for reasons of

- victim and/or community safety, then the police must not carry out the warning. (See option below)

Before and after police give the warning, they must let the victim know.

- Warnings have helped prevent escalation in some cases overseas.

- It must be clear that police have the power to arrest a stalker who has not been given a warning if the criteria for illegal stalking have been met. Police must investigate whether stalking criteria are met even if no warning has been given, rather than assuming that without the warning, there is no evidence the stalker knows their behaviour is likely to cause fear or distress

- Police need to take victim views into account to ensure that warnings are highly likely to make victims safer, and not put them further at risk. There are a range of opinions as to whether or not a victim’s preference for the police not to give a warning should always be followed.

- Before police give the warning, they must let the victim know a warning is to be given and when it is likely to be delivered, and then as soon as possible after the warning has been given, the police must let the victim know that the warning has been delivered, to mitigate distress and anxiety.

Mauri ora! Thank you for informing Aotearoa’s new stalking law for the hauora and wellbeing of all our communities.

National Helplines

Please be aware that you may have to wait on hold before someone answers your call.

- Shine Domestic Abuse Helpline24/7 – webchat available 0508 744 633

- Women’s Refuge– 24/7 phone and webchat available 0800 733 843

- HELP sexual abuse helpline 24/7 phone and text available 0800 623 1700 text 8236

- Safe to Talk – 24/7 Sexual harm support – phone 0800 044 334

In addition to the national helplines above, Hohou Te Rongo Kahukura offer resources by and for Takatāpui and Rainbow communities, about family, partner and sexual violence, and free, confidential, mana-enhancing support and recovery services for Takatāpui and Rainbow survivors, partners and whānau. kahukura.co.nz